Remembering the Diplomats on Memorial Day

Every year on Memorial Day, American flags are flown to honor members of the U.S. Armed Forces who died or were wounded in the line of duty. Their service is noble, and I appreciate that our country publicly acknowledges their sacrifices.

Scant attention, however, is paid to the civilians who serve courageously in the line of fire. Diplomats and other civilians who work for the U.S. government are often placed in dangerous and unstable locales around the world. They have participated in every war and conflict since the Revolutionary War alongside their military colleagues. In some cases, the civilians stayed behind after the troops withdrew, as happened last year in Iraq. They were also stationed in places without the benefit of U.S. military support when unrest occurred, as happened in Libya, Syria, and in other countries that experienced upheaval during the Arab Spring.

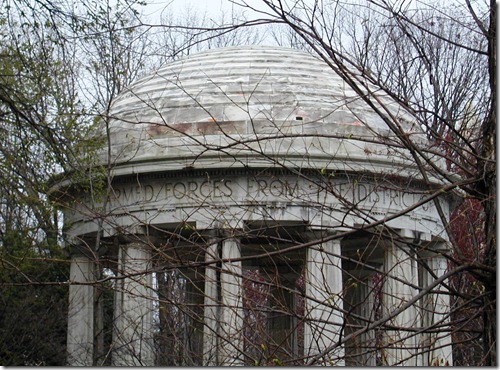

Hundreds of American diplomats have died in the line of duty. Their deaths were caused by natural disasters, diseases, killings, assassinations, and trying to save others’ lives. Two memorial plaques in the entrance hall of the State Department list the names of the 231 diplomats who have died in the line of duty since William Palfrey was lost at sea in 1780. More recently, Brian Adkins was killed in his home in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in 2007, and David Foy was killed in 2006 by a car bomb in Karachi, Pakistan. This figure does not include the 52 Americans held hostage for 444 days during the 1979-80 Iran Hostage Crisis when students and militants overran the then-U.S. Embassy in Tehran. The International News offers a sobering analysis of the history of violence against American diplomats, reporting that 111 have been killed or assassinated since 1780. According to the State Department, more ambassadors than U.S. generals or admirals have been killed since World War II. The U.S. Diplomacy Project tells the tales of diplomats who were put in harm’s way while serving overseas.

While 231 may not sound like a large number, consider that at any given time there are only about 11,000 American diplomats versus the more than 2.5 million members of the U.S. Armed Forces. A rough comparison of casualties during the Iraq War in 2008 revealed that personnel working for the State Department in Iraq during 2003-08 had a casualty rate of about 50% that of their military counterparts. As the events of September 11, 2001, showed, you don’t have be involved in active combat to be a casualty of war and terrorism.

While 231 may not sound like a large number, consider that at any given time there are only about 11,000 American diplomats versus the more than 2.5 million members of the U.S. Armed Forces. A rough comparison of casualties during the Iraq War in 2008 revealed that personnel working for the State Department in Iraq during 2003-08 had a casualty rate of about 50% that of their military counterparts. As the events of September 11, 2001, showed, you don’t have be involved in active combat to be a casualty of war and terrorism.

Civilians who serve our country overseas work for the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and other U.S. Government agencies or as contractors. Many support the U.S. military and diplomatic corps in hostile and dangerous conditions. They are unsung heroes who are rarely featured on the evening news or in movies. They labor in obscurity to protect the freedoms that Americans enjoy.

The Uniform Monday Holiday Act (Public Law 90-363) set aside Memorial Day as a federal holiday to be celebrated each year on the last day of May. The law, however, does not specify who or what it commemorates. That’s up to you to decide. In the minds of many Americans, Memorial Day is a day to honor the U.S. Armed Forces, but this was not always so. The holiday known in the late 1800’s as Decoration Day recognized the veterans of the Union Army who fought in the American Civil War. After World War I, the generally accepted meaning of the day was to honor all Americans, military or civilian, who died in any war. This changed following World War II. It’s time to return to the days when we acknowledged the efforts of all who serve their country bravely in and out of uniform.

This Memorial Day, amid the barbeques, car races, fireworks, and gatherings, remember the diplomats and other civilians who faithfully serve their country in harm’s way.

Happy Memorial Day. God bless America, and God bless those who serve our country.

Click here to read my 2007 post on Memorial Day.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of State. The photos belong to the author.