Wat Yai Chai Mongkhon in Ayutthaya, Thailand

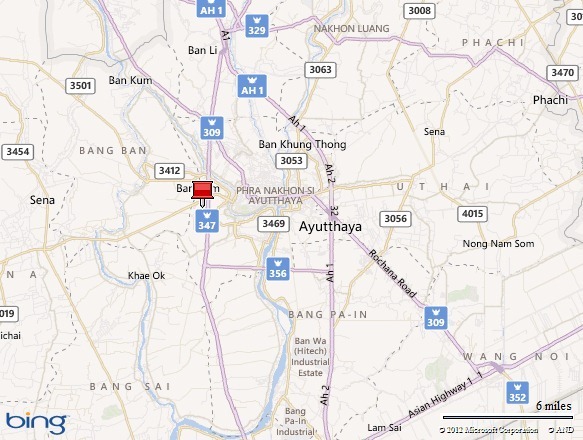

This is the fourth in a five-part series on Ayutthaya, Thailand about Wat Yai Chai Mongkhon, a restored Buddhist temple dating back to the Ayutthaya Kingdom period (1350-1767). The first article described the historic City of Ayutthaya; the second, the temple ruins of Wat Chaiwatthanaram, and the third, Wat Phu Khao Thong. The final post will feature the ruins of temple Wat Mahathat.

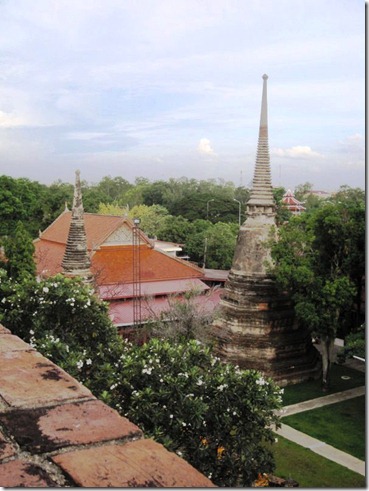

Wat Yai Chai Mongkhon, or the “Great Monastery of Auspicious Victory” according to the website History of Ayutthaya, is a restored Buddhist temple located in southeast Ayutthaya. Evidence of a large moat that once existed around the site suggests that it was once an important Khmer-style temple complex in “Ayodhya,” a settlement that pre-dated the Ayutthaya Kingdom. Today it’s a functioning temple with a monastery and restored stupa or chedi (monument). Several smaller chedi ruins dotting the grounds serve as a reminder that the site is historical.

Records indicate that Ayutthaya King Uthong, or Ramathibodhi I (1350-69), established the monastery to lay to rest two of his children, Chao Kaeo and Chao Thai, who died of cholera. Its first name was Wat Pa Kaeo or the “Monastery of the Crystal Forest.” The temple built on the site later became known as Wat Chao Phya Thai, or the “Monastery of the Supreme Patriarch,” and was home to monks trained in then-Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka).

The temple is noteworthy in Ayutthaya’s history for its role as a meeting place for conspirators involved in palace intrigue. Stories suggest that it was once home to a closely-guarded, priceless ruby that represented the wealth of the gods. In his chronicle of the history of Ayutthaya, Jeremias Van Vliet, an employee of the Dutch East India Company, alleged that slaves were groomed to die in mock attempts to steal the ruby as an offering to the gods.

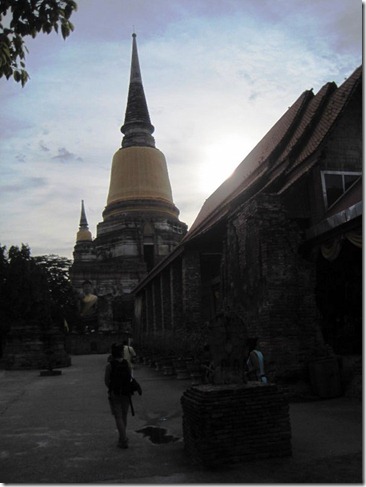

The current configuration of the temple and chedi took shape during the reign of King Naresuan (1590-1605), who reportedly gave it the name “Wat Yai Chai Mongkhon” to commemorate his victory over the Burmese occupiers he ousted from Ayutthaya in 1592. The temple was destroyed by the Burmese in 1767 and restored by the Thais in 1957. The tall chedi that stands an estimated 30 meters (100 feet) is almost as high as the one at Wat Phu Khao Thong; its more slender profile that rises in the middle of urban Ayutthaya obscures its true height.

The temple is perhaps best known for its seven-meter (23 feet) long reclining Buddha constructed during King Naresuan’s reign. One of the largest outdoor reclining Buddhas in Thailand, it was restored in 1965 and is now a major tourist attraction in Ayutthaya.

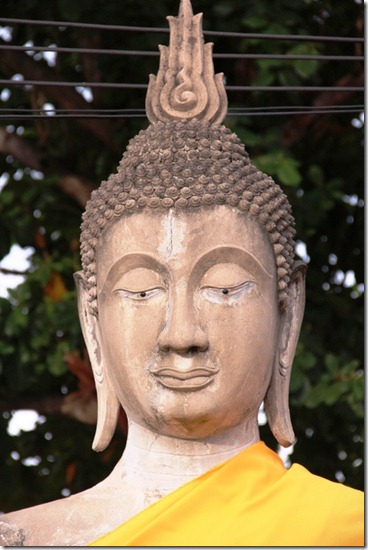

The large chedi that dominates the temple complex has a square base with smaller chedi on each corner. It rises to a platform with great views of the city. As you ascend the steps, a large Buddha statue greets you at the top with a calm nod. Above the platform rises a bell-shaped tower with an octagonal base that tapers to a point; a chamber on the western side with Buddhist relics serves as a prayer shrine. The temple complex unfolds below in all directions, from the monks’ quarters and ordination hall to the west to a garden with several large Buddhist statues to the east. Manicured lawns with groomed trees and ruined chedi grace the north and south flanks.

During my visit to the temple in August 2012, I was struck by the number and symmetry of the Buddha statues that meditated around the chedi base. Some such as those in the nearby prayer shrine were unique, but most were virtually identical and sat at attention in a tantric state. My wife did an excellent job capturing this impression with photos of them at artistic angles.

Wat Yai Chai Mongkhon was the last stop on our daytrip to Ayutthaya. We enjoyed watching the encroaching dusk transform the temple from a place that beckoned visitors to one reclaimed by shadows. The site is a great destination to end the day before going for dinner and embarking on an evening tour of the city to see the historic monuments of Ayutthaya at night.

More About Ayutthaya, Thailand

Click here to read about the City of Ayutthaya and the Ayutthaya Historical Park

Click here to read about Wat Chaiwatthanaram, the ruin of a former Buddhist temple

Click here to read about Wat Phu Khao Thong, a historical Buddhist monastery

Click here to read about Wat Mahathat, the ruin of a former Buddhist temple

M.G. Edwards is a writer of books and stories in the mystery, thriller and science fiction-fantasy genres. He also writes travel adventures. He is author of Kilimanjaro: One Man’s Quest to Go Over the Hill, a non-fiction account of his attempt to summit Mount Kilimanjaro, Africa’s highest mountain and a collection of short stories called Real Dreams: Thirty Years of Short Stories. His books are available as an e-book and in print on Amazon.com and other booksellers. He lives in Bangkok, Thailand with his wife Jing and son Alex.

M.G. Edwards is a writer of books and stories in the mystery, thriller and science fiction-fantasy genres. He also writes travel adventures. He is author of Kilimanjaro: One Man’s Quest to Go Over the Hill, a non-fiction account of his attempt to summit Mount Kilimanjaro, Africa’s highest mountain and a collection of short stories called Real Dreams: Thirty Years of Short Stories. His books are available as an e-book and in print on Amazon.com and other booksellers. He lives in Bangkok, Thailand with his wife Jing and son Alex.

For more books or stories by M.G. Edwards, visit his web site at www.mgedwards.com or his blog, World Adventurers. Contact him at me@mgedwards.com, on Facebook, on Google+, or @m_g_edwards on Twitter.