Verda is one of the stories in Real Dreams: Thirty Years of Short Stories. It is also available to read on Wattpad.

A Brief History of Verda

She rises in the evening sky like a beautiful green gem glowing in the early twilight. Watching over the earth, she bathes it in verdant light at the end of each day. She lies closer to our world than her barren twin, Luna, who shines brighter when the twilight turns to night. She is Verda, the green-tinged moon that orbits the earth. Also known as “Earth’s Sister,” the small moon has long been an object of human obsession. For millennia, people have gazed up at her and wondered what secrets she has hidden in her veiled green atmosphere. It was not until the late twentieth century at the dawn of the Space Age, however, that many of her secrets were revealed.

People have wondered throughout history about the nature of Verda and marveled at her many faces. To some, she represented the image of perfection, a glimpse of what the earth once was but had lost since the rise of humanity. Phoenicians, Mayans, and other cultures believed her to be a feminine deity. The Greeks called her “Adelfigea,” the sister of the Earth-goddess Gaea, and believed that she watched over us like a maternal figure. Buddhists considered the green moon a celestial manifestation of Nirvana, while to some Christians she symbolized heaven.

Some have defined Verda using scientific theory. The Greek astronomer Ptolemy hypothesized in 131 A.D. that the moon’s green luster derived from vegetation growing on her surface. In 1514, the Italian astronomer Copernicus theorized that she was not a planet, as was previously believed, but a moon that revolved around the earth, like her gray twin Luna. In 1609, after the advent of long-distance telescopic lenses, the Italian astronomer Galileo mapped some of Verda’s surface features. It was he who gave her the name by which she is best known. Johannes Hevelius, a German brewer by trade, published the first maps of the Verdan surface in his lunar atlas, “Selenographia,” in 1647. In 1891, Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli offered the first telescopic evidence of the existence of vegetation on Verda, affirming Ptolemy’s hypothesis. The discovery fueled scientific debate over whether she could sustain human life. American Astronomer Percival Lowell published a thesis in 1899 outlining a process for colonizing her, a prescription the United States and other countries followed just six decades later.

For centuries, mankind pondered the possibility of exploring and living on Verda but lacked the technology to achieve it. Following World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union embarked on ambitious space programs designed to send astronauts to the Earth’s twin moons. The United States’ predecessor to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, concluded in 1957 that unlike her barren twin, the green moon’s atmosphere was comparable to the Earth’s and that settlement was possible. Scientists determined that Verda, less than 1/6 the size of Earth with a circumference of just 7,000 kilometers (4,400 miles) at the equator, could sustain human life. Her atmosphere was 24.2% oxygen and 74.3% nitrogen, comparable to that of the earth, and she had robust seasonal changes.

The Soviets won the race to Verda, landing an unmanned rocket, Versta I, on her in 1958. Although the craft crash landed, it was able to transmit to Earth the first recorded data from the surface. The Soviets and the Americans undertook three missions each to Verda over the next decade, sending modular probes to research the moon’s air, water, and soil composition. The results of the Soviet Versta III and IV missions and the American Athena II and III missions showed that the green moon’s atmosphere was hospitable. They concluded that the climate was moderate and the air breathable. Because they observed only pockets of water on the surface, moderate precipitation, and limited cloud cover, scientists conjectured that she was fed primarily by large underground aquifers.

The Soviets won the race to Verda, landing an unmanned rocket, Versta I, on her in 1958. Although the craft crash landed, it was able to transmit to Earth the first recorded data from the surface. The Soviets and the Americans undertook three missions each to Verda over the next decade, sending modular probes to research the moon’s air, water, and soil composition. The results of the Soviet Versta III and IV missions and the American Athena II and III missions showed that the green moon’s atmosphere was hospitable. They concluded that the climate was moderate and the air breathable. Because they observed only pockets of water on the surface, moderate precipitation, and limited cloud cover, scientists conjectured that she was fed primarily by large underground aquifers.

After several failed attempts by the Americans and Soviets to send manned missions to Verda, astronauts first landed on her during NASA’s 1967 Artemis I mission. Five Americans, Scott Rhodes, Steve Blair, Larry Smith, John Keller, and Donald Acheson, touched down on September 6, 1967. The Artemis I rocket released a landing module carrying the astronauts and then burned up in the atmosphere. Although the capsule landed safely and the crew survived the impact, they knew that NASA could not bring them home because the gravitational pull on Verda was too strong. The United States undertook the mission after calculating that the astronauts could survive on their own until NASA developed the capability to bring them back to Earth. The space agency prepared a contingency plan to deliver emergency supplies to the astronauts until it could develop a feasible solution to bring them home.

The Artemis I module crashed on the rocky surface between the moon’s equator and north pole in the region scientists thought most capable of sustaining life. Her atmosphere was somewhat thinner than that of Earth and akin to living at high altitudes. Nevertheless, the astronauts could breathe without oxygen. The surface temperature on Verda read nine degrees Celsius (48 degrees Fahrenheit). The terrain where they landed was rugged with a plateau hemmed in by mountains. The astronauts thought that the cool landscape looked like tundra. The sparse plant life looked vaguely familiar, although they assumed that the species were indigenous.

Team leader Donald Acheson took the first step on Verdan soil on September 7. He donned his space suit and descended to the surface. Millions of viewers around the world watched as Steve Blair filmed him leaving the capsule. A spectacular view of the Earth and half of Luna served as a poignant backdrop. Acheson stood on the edge of the lander and said, “One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” The words were beamed to the NASA Space Center in Houston and broadcast worldwide.

Acheson lowered himself from the module and stepped on the surface. He thought he had touched the earth! The gravity had less pull than at home, but he was far from weightless. He looked around at the inviting landscape and felt awkward in his space suit. He wanted to take it off and put on a light jacket. He announced, “Houston, I will now attempt to breathe on my own.”

He released his pressure helmet from the neck ring. Air pressure escaped from his suit. For a moment Acheson panicked, fearing that the modular instruments were incorrect and that he would suffocate from breathing in an unknown atmosphere. Holding his breath, he took off his helmet and felt cool air brush against his face. Then he took a breath and held it in for a few seconds. Exhaling, he said into the microphone embedded in his helmet, “I can breathe, Houston. Welcome to our new home away from home. The weather here is great.”

Acheson thought he heard the entire world applauding and whistling. A few minutes later, three more astronauts emerged wearing space suits with helmets in hand. One stayed in the capsule as a precaution. The astronauts looked around and marveled at this place that seemed so much like Earth. They had taken some measures to protect their skin from radiation and lungs from poisonous gasses, but they felt great. They wouldn’t know for some time whether exposure to Verda’s atmosphere was dangerous but realized that this moment was a critical step forward in their understanding of the green moon and of space.

The team of astronauts settled in on Verda for three months before they were joined by a crew of ten astronauts from the Artemis II mission. Together the teams surveyed the area and studied plant life, rock formations, and soil composition. The rock and soil samples showed that the surface was very similar to the earth’s. They discovered new species of plants, bacteria, microbes, and minerals but could not locate any animal life. Humans seemed to be the first animals to inhabit the moon’s ecosystem. They found some standing water but no rivers or lakes. Infrequent precipitation fell as snow mixed with rain and sleet.

The astronauts from Artemis I and II had arrived on the green moon during late summer. Unless more supplies arrived soon, they would have to survive on their own during the winter in a new and unfamiliar environment. They hunkered down, turning the two Artemis capsules into shelters and using large rocks to build makeshift buildings. A shrub native to Verda burned well and served as a good fuel source. Some plants the astronauts deemed edible supplemented their steady diet of space food. They drilled a well with tools sent by NASA and struck water about 50 feet below the surface. The water was pure enough to drink without boiling.

NASA sent two unmanned missions to Verda with enough supplies to get the astronauts through the winter. One of the capsules landed several miles from the astronaut’s landing site, and three astronauts died in a freak winter storm while trying to retrieve its contents. The remaining astronauts set their research aside and focused on surviving the hostile winter that lasted eight months, much longer than on Earth as the Verdan year was sixteen months long. NASA kept in close contact with them through radio and television transmissions and helped troubleshoot issues but was limited in what it could do to assist. Millions of people tuned in to a weekly television program documenting the men’s quest to survive. Six astronauts died during that first winter, including two who contracted an indigenous, flu-like illness. The astronauts were vulnerable to illnesses because their immune systems lacked the proper antibodies. Winter passed, and summer returned. NASA sent a third manned mission to the moon to relieve the nine survivors. The astronauts celebrated the change of seasons and their survival with their own rendition of Thanksgiving. They dined on rations and native grass stew, a far cry from the Pilgrim’s feast.

Following the historic success of the Artemis project, the U.S. government drew up plans to establish a permanent base on the green moon. Not far behind, the Soviet Union drew up its own plans for settlement, and the Japanese, British, and French tinkered with the idea of sending their own missions. By 1968, fifty more American astronauts joined the survivors and established a new base called Artemis Camp near the site of the Artemis I landing. They chose a more suitable location in a ravine that protected it from the Verdan winds. NASA sent four more missions between 1968 and 1969, with enough supplies and materials to establish a permanent presence. The unmanned modules yielded scrap metal and other components that the astronauts recycled into building materials. Although the agency planned to build a command center on Verda capable of sending the astronauts back to Earth, it had not yet developed the technology to counteract the effects of gravity. All astronauts who volunteered for a mission to the green moon knew that they would remain there long term—or perhaps never return. The medical clinic in Artemis Camp was not equipped to treat astronauts in life-threatening situations. Fourteen astronauts died in the early years from injuries and medical emergencies, including asphyxiation and the outbreak of a lethal virus native to Verda. Those exposed were quarantined for months until the epidemic subsided.

In late 1968, the Soviets successfully landed the Novaya Zemlya I rocket on the far side of Verda, more than 1,000 miles from the Artemis site. They established Brezhnevskaya, a base that grew to over a hundred astronauts and scientists by 1985s. Artemis Camp had little contact with the Soviet base in its early years, and the two worked independently.

A new era of colonization began, and the race to develop Verda heated up between the Soviets and the Americans. They and other nations signed the 1967 Outer Space Treaty to limit the use of Luna, Verda, and other celestial bodies to peaceful purposes and to prohibit sovereignty claims. However, the agreement did not stop countries from exploiting its resources. Unlike Antarctica, where countries conducted peaceful research under the Antarctica Treaty System, Verda was considered a resource-rich prize coveted by many countries, despite repeated attempts by the United Nations (UN) to declare it an internationally-protected territory. Between 1968 and 1985, the UN proposed a declaration several times to protect the moon from exploitation. Each year, members of the UN Security Council vetoed the measure.

In the early 1970s, the United States, with the help of Japan and its NATO allies, launched a series of Gaea-class rockets to provide materials and manpower to the more than a hundred astronauts living and working in Artemis Camp. The base in the early-to-mid 1970s looked like an Antarctic outpost with clusters of buildings devoted to research, living quarters, a medical clinic, and a mess hall. Astronauts installed windmills and solar panels to generate electricity for the complex. They built greenhouses using materials imported from Earth and raised indigenous plants for food. No known animals were native to Verda, so inhabitants ate vegetarian meals except for the occasional meat brought from Earth. The animals and non-native plants introduced to the green moon remained in quarantine; the astronauts were determined not to introduce any alien life forms except themselves.

The Gaea rockets carried payloads that would lay the groundwork for NASA’s Artemis Command Center. The mounting costs of repeated missions led the United States to include Japan and its European allies in its space efforts. By the mid-1970s, Artemis Camp began to resemble an international compound, and a unique culture emerged. Residents often gathered in the mess hall, affectionately known as the “Green Room,” to watch European soccer, American football, and Kurosawa films over peet, an indigenous homebrew. They observed Landing Day on September 7 and various national holidays. Although life grew more comfortable for the astronauts as time passed, many still experienced the psychological stress of living in space separated from their loved ones.

In 1977, NASA announced the development of the first working prototype of a space shuttle capable of landing on Verda. It lacked the crucial ability to return to Earth, although it brought the agency’s space program closer to its goal. The shuttle Columbia made the voyage to Artemis Camp in 1979 and never returned. Scientists converted the shuttle into an intra-space transport, and it flew several missions over Artemis Camp, mapping Verda’s terrain in tandem with Sagittarius-class satellites orbiting the moon. Five other space shuttles incapable of landing or returning to Earth, Atlantis, Challenger, Discovery, Endeavor, and Enterprise, never made the trip to Verda.

In the 1980s Artemis Camp took on the air of a colony. While NASA and its partner agencies had the ultimate say in decisions involving Verda, those who lived there established the Camp Council to deal with day-to-day governance and internal affairs. They elected Donald Acheson to serve as their leader until his fatal heart attack in 1985. The council tried to make life as normal as possible for residents. An ethical conflict erupted in 1983 when the family of John Keller, one of the original astronauts, sued NASA to allow his wife Jan to join him at Artemis Camp after 16 years of separation. Their case was dismissed. Another astronaut, Bob Morris, suffered a nervous breakdown and had to be quarantined for two years in 1985 after assaulting a teammate. The psychological stress of living in space, unable to return home, took an immense toll on those stranded on Verda. NASA developed a program to treat astronauts for stress after the Morris Incident with some success.

The first spacecraft designed to return to Earth flew round trip to the green moon on July 4, 1987, almost two decades after the first landing. The next-generation shuttle, christened the Victory, landed at Artemis Camp on July 2. It was equipped with internal propulsion and booster engines capable of breaking free of the Verdan atmosphere and reentering Earth’s. The first female astronauts, Tracy Murray, Wilma Adams, and Barbara Stein, arrived, and the two surviving astronauts from Artemis I, John Keller and Scott Rhodes, returned to Earth. After a tearful farewell watched by millions of television viewers, the Victory touched down at Edwards Air Force Base two days later with sixteen astronauts who had not been back to Earth for almost 20 years. The reunion of John and Jan Keller, whose unsuccessful lawsuit made the couple famous, was seen by millions around the globe.

The Victory made several round trips in the decade that followed, bringing back all astronauts who had lived in Artemis Camp longer than one year. NASA’s development of a reusable vehicle capable of returning to Earth put the Soviets at a major disadvantage. Economic stagnation in the Soviet Union during the 1980s limited its ability to counter the Americans’ huge technological leap, and it opted to negotiate an agreement with the United States. In 1987, President Ronald Reagan and General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev signed the Strategic Agreement on Verdan Development (SAVD), pledging mutual cooperation on the moon. The Americans established an air link between Artemis Camp and Brezhnevskaya. The Columbia served as a biweekly transport between the two bases. The Soviets shared technologies and techniques that improved agriculture and operations in Artemis Camp.

Three other next-generation shuttles joined the Earth-Verdan fleet: Liberty in 1988, Constitution in 1989, and Monitor in 1990. The four shuttles made 30 round trips between 1987 and 1991, making travel to and from the moon a relatively routine journey. On August 5, 1991, however, tragedy struck when the Liberty disintegrated upon entry into the Verdan atmosphere, killing all 20 astronauts aboard. Government officials concluded that a malfunction in the shuttle’s insulation caused it to explode. NASA suspended all shuttle missions, including Columbia flights, during its 15-month investigation, stranding more than 250 scientists at Artemis Camp. The base was self-sufficient enough to survive in isolation for an extended period of time. During the hiatus, a team of scientists made the groundbreaking 1,000-mile overland trek to Brezhnevskaya to obtain emergency medication for a colleague stricken with cancer.

Economic development flourished on Verda in the 1990s and focused largely on petroleum and mineral exploration as well as the establishment of refineries capable of producing rocket fuel. Energia, an international base established by the United States, the Europeans, and the Russians, was built on the site of a large petroleum reserve over 350 miles from Artemis Camp. The private sector began to invest in projects on Verda and accelerated its push into the moon in the late 1990s, hoping to capitalize on its abundant and lucrative natural resources. The race to exploit the moon became so intense that in 1998, on the heels of the Kyoto Protocol, 48 nations signed the Verda Treaty System to regulate activity on Verda. The UN approved for the first time a resolution to protect and preserve the green moon.

What had once been an object of mystery and wonder was transformed in just five decades into a finite place defined by her scientific, economic, and political value. What was seen as a heavenly body watching over the earth had been reduced to a territory to be conquered and exploited. Coveted for what she could give, those who ventured to Verda learned to respect her after she took a heavy toll on them. Fewer than 75 percent of those who went to the green moon survived the ordeal. While exploration helped increase people’s understanding of space and of the universe, it came at a cost. From Acheson, who died on Verda and never saw his family face to face again, to those who lost their lives from epidemics or disasters, the tale of Verda has been and remains one of triumph and tragedy.

More About Verda and Real Dreams

Click on the icons below

[table “” not found /]

© 2014 Brilliance Press. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted without the written consent of the author. This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental. Cover photo licensed from iiuri courtesy of Shutterstock.

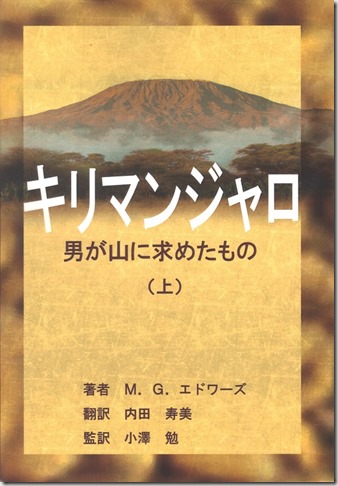

世界冒険シリーズ第一弾『Kilimanjaro: One Man’s Quest to Go Over the Hill』には、私自身がアフリカ最高峰キリマンジャロへ挑戦した記録が記されています。当事40歳だった私は、中年の危機に直面していました。そこで、生活を一新するためにキリマンジャロへの挑戦を決意しました。本書は中年になった私が挑戦したキリマンジャロ制覇までの道のりとその他の様々な試練を乗り越えた現実の記録です。当事、私は外交官としての仕事に行き詰まり、迷いとストレスを感じる日々を過ごしていました。そして2010年、新しい生活へ向かって飛び立つために、アフリカ最高峰であるキリマンジャロに挑戦することを決心しました。中年になってから、長年勤めた外交官を辞めて自分の夢を追いかけることには大きなためらいがあります。私にとっては巨大な挑戦であるキリマンジャロを制覇することができたら、著作業という自分の夢に向かって進んでいく不屈の精神を養えるに違いない。私はそう信じていました。2010の終わりに大いなる希望を抱いてスタートした登山ですが、すぐにキリマンジャロへ登ることがいかに困難であるかという現実に直面しました。「全ての人のエベレスト」として知られているこの山の山頂までの道のりは、これまで私が乗り越えてきた至難と比べ物にならないほど、想像を絶する試練でした。頂上に達するどころか、生き延びるために奮闘しなくてはならなかったのです。精神的かつ肉体的な強靭さを必要とするキリマンジャロ登山は、私の人生の最大の挑戦でした。この記録は、中年になったと感じ、困難に直面することがあっても生活を変える勇気が必要な人たちに是非読んでいただきたいと思っています。また、世界的に高い山々に登山しようと考えているアマチュア登山家達の参考にもなるはずです。キリマンジャロ登山への計画をじっくりと練ってから挑戦した私自身の考察やアドバイスが一杯詰っている本書は、キリマンジャロに登ろうと考えている読者に実行に踏み出す勇気を与え、様々な困難を乗り越えて頂上に達する助けになるでしょう。『Kilimanjaro: One Man’s Quest to Go Over the Hill』は2012年グローバル電子書籍賞佳作賞を受賞しました。私自身が登った登山路の写真も60枚以上掲載されています。

世界冒険シリーズ第一弾『Kilimanjaro: One Man’s Quest to Go Over the Hill』には、私自身がアフリカ最高峰キリマンジャロへ挑戦した記録が記されています。当事40歳だった私は、中年の危機に直面していました。そこで、生活を一新するためにキリマンジャロへの挑戦を決意しました。本書は中年になった私が挑戦したキリマンジャロ制覇までの道のりとその他の様々な試練を乗り越えた現実の記録です。当事、私は外交官としての仕事に行き詰まり、迷いとストレスを感じる日々を過ごしていました。そして2010年、新しい生活へ向かって飛び立つために、アフリカ最高峰であるキリマンジャロに挑戦することを決心しました。中年になってから、長年勤めた外交官を辞めて自分の夢を追いかけることには大きなためらいがあります。私にとっては巨大な挑戦であるキリマンジャロを制覇することができたら、著作業という自分の夢に向かって進んでいく不屈の精神を養えるに違いない。私はそう信じていました。2010の終わりに大いなる希望を抱いてスタートした登山ですが、すぐにキリマンジャロへ登ることがいかに困難であるかという現実に直面しました。「全ての人のエベレスト」として知られているこの山の山頂までの道のりは、これまで私が乗り越えてきた至難と比べ物にならないほど、想像を絶する試練でした。頂上に達するどころか、生き延びるために奮闘しなくてはならなかったのです。精神的かつ肉体的な強靭さを必要とするキリマンジャロ登山は、私の人生の最大の挑戦でした。この記録は、中年になったと感じ、困難に直面することがあっても生活を変える勇気が必要な人たちに是非読んでいただきたいと思っています。また、世界的に高い山々に登山しようと考えているアマチュア登山家達の参考にもなるはずです。キリマンジャロ登山への計画をじっくりと練ってから挑戦した私自身の考察やアドバイスが一杯詰っている本書は、キリマンジャロに登ろうと考えている読者に実行に踏み出す勇気を与え、様々な困難を乗り越えて頂上に達する助けになるでしょう。『Kilimanjaro: One Man’s Quest to Go Over the Hill』は2012年グローバル電子書籍賞佳作賞を受賞しました。私自身が登った登山路の写真も60枚以上掲載されています。