Elvis in Africa

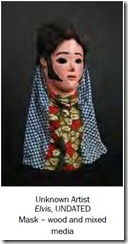

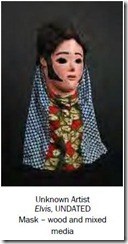

One day not long ago, I first encountered what I thought was a bust of Elvis Presley. His image was unsettling, as if his face had been surgically removed a la the movie “Face/Off.” I soon realized that it was a handmade ceremonial mask of “The King” made in the Chewa tradition. I thought it odd that the Chewa people of central and southern Africa would fashion a mask honoring a 1950s American music icon. What I initially found creepy – to be honest – has now become an intriguing fixture in my life. “Elvis” now pops up in mysterious places at odd times as if possessed by a ghost or repositioned by a trickster. One never knows when Elvis will be sitting in front of a podium ready to deliver a speech or at the water fountain waiting for a drink.

One day not long ago, I first encountered what I thought was a bust of Elvis Presley. His image was unsettling, as if his face had been surgically removed a la the movie “Face/Off.” I soon realized that it was a handmade ceremonial mask of “The King” made in the Chewa tradition. I thought it odd that the Chewa people of central and southern Africa would fashion a mask honoring a 1950s American music icon. What I initially found creepy – to be honest – has now become an intriguing fixture in my life. “Elvis” now pops up in mysterious places at odd times as if possessed by a ghost or repositioned by a trickster. One never knows when Elvis will be sitting in front of a podium ready to deliver a speech or at the water fountain waiting for a drink.

No one knows when the mask was made or who made it. It was most likely made by a Chewa artist. Their masks have been an important part of performances of the secretive Nyau society. Information on Nyau dancing indicates that: “Masquerade is a complex art form involving many parts: costumes and masks, music, choreography, lyrics, and the ambient situation (location, weather, time of day, etc.) Masquerade has apparently existed in Africa for millennia, and it is still actively practiced today. Dances and masks have different meanings for different audiences: some are secret, and some public, with layers of meaning for different audiences.’ The Chewa Elvis masquerade of Zambia and Malawi developed after the American singer became well known in Africa in the 1950s and 1960s. All Elvis masks include certain elements: a thick, pompadour wig, long lamb-chop sideburns, bright, pale skin, a narrow upturned nose, and thick, slightly parted lips. The dancers, always young males, perform a provocative, gyrating choreography mimicking Elvis Presley’s famous hip movements. The masquerade is an example of how African traditional art forms have evolved over time, with interesting changes in the last century, particularly with the advent of international communications.”

Nyau traditions of the Chewa people may be shrouded in mystery, but one thing is certain: Elvis is alive and well in Africa.

Special thanks to Janet Peterson for contributing information used in this posting.

[table id=13 /]

[wpgmza id=”5″]

[table id=8 /]